METAL ECONOMY

More than 80 of the 92 naturally occurring elements are found in living organisms, but 12 of the low mass elements, which are also high abundance elements on Earth, constitute > 99% of the biomass. Yet, the others, despite their occurrence at trace levels, are essential for life because they enable the diverse chemistries of living cells. Organisms use metals like copper, iron, manganese, molybdenum, vanadium, which have multiple stable oxidation states, for reducing nitrogen gas to ammonium, for using light to convert carbon-dioxide and water to carbohydrate, and for extracting energy from inorganic or organic chemicals to sustain life. At the same time, their reactivity can make these very elements harmful in the biological environment, especially in the presence of oxygen. Too little means that enzymes that use the trace metals as catalytic cofactors will not function, and too much means that the metals may react promiscuously.

For this reason, there are homeostatic mechanisms to maintain elemental quotas in biology. One evolutionary adaptation to limitation in a particular element is the reduce, reuse, recycle paradigm. For instance, when faced with Fe deficiency, an organism can reduce its inventory of iron-containing proteins by replacing them with iron-independent catalysts. In situations of Fe starvation or sustained deficiency, an organism can remove Fe from one protein and reuse it in a different – more critical for life – protein. These mechanisms have been discovered through classical genetics and biochemistry in multiple microbes, revealing metabolic signatures for elemental economy. Comparative genomics and metagenomics indicate widespread utilization of these economies in nature.

We use Chlamydomonas reinhardtii as a reference system for dissecting the signaling pathways involved in metal sensing, sparing and homeostasis in the context of chloroplast biology and photosynthesis.

Also see Merchant, S.S., Helmann, J.D. (2012) Elemental economy: microbial strategies for optimizing growth in the face of nutrient limitation. Adv. Microbiol. Physiol. 60: 91-210 for more information.

Photosynthesis and comparative algal genomics

Algae are distributed throughout the tree of life with polyphyletic origin; their defining characteristic is the presence of a photosynthetic plastid. There is remarkable diversity among the algae. They inhabit temperate and tropical soils and fresh waters, polar permafrost, as well as marine environments. Extremophile algae, like Dunaliella species, may inhabit the oversaturated salt lakes or acid lakes at pH 0! Advances in sequencing technology and computational methods are giving us a breadth of genomic data that can be used to understand the breadth of metabolism in this important group in the microbial world.

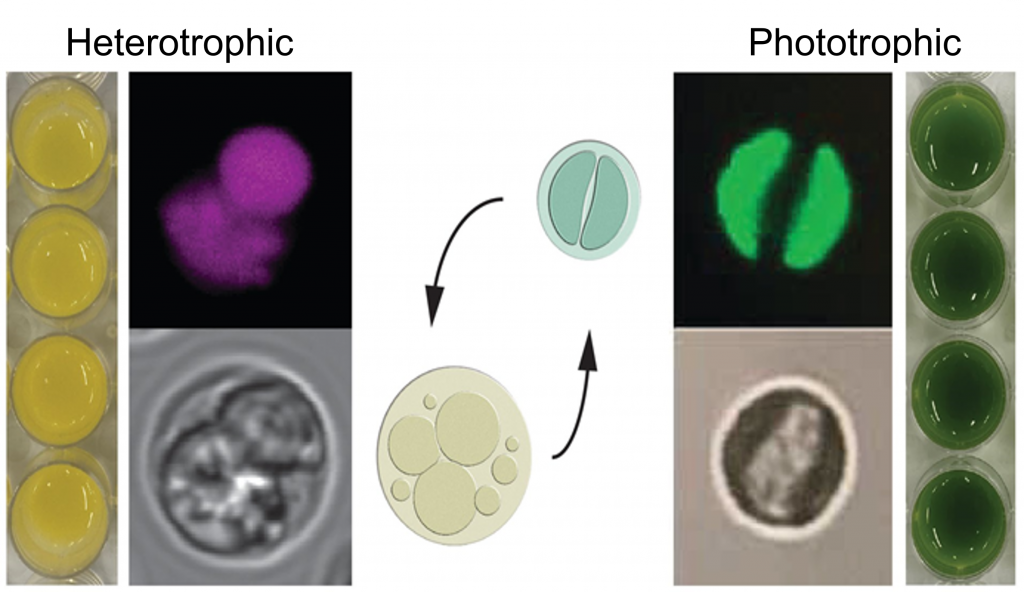

The proteomes of diverse algae can be used to infer a paleontological record of environments experienced by their ancestors. Algae in Archaeplastida contain primary plastids that originated from an endosymbiotic relationship with a cyanobacterium. These algae share a common ancestor with land plants. Outside this group, there are algae that originated from one or more endosymbiotic relationships with a eukaryotic alga, giving rise to organisms with secondary or tertiary plastids. Among the algae in Archaeplastida are Chlamydomonas, a key reference organism for fundamental discovery in photosynthesis and chloroplast metabolism, halotolerant Dunaliella spp., of commercial interest as a rich natural source of beta-carotene, and Chromochloris zofingiensis, which we are lifting up as a biofuels reference organism for its remarkable capacity for accumulating triacylglycerols (biodiesel precursors).

For each organism, we have high quality chromosome-level genome assemblies, and transcript-based structural annotations. For Chlamydomonas, we use highly synchronized cultures in flat panel bioreactors to generate multi-layered genome-wide datasets anchored to physiology to dissect daily metabolic rhythms and patterns. Similar approaches in Chr. zofingiensis will enable the application of synthetic biology in phototrophs for biofuels and high value bioproducts. For Dunaliella, our interest is in using cryo-EM approaches to get a view of the dynamics of the photosynthetic apparatus during acclimation to extreme environments.

Also see Blaby-Haas, C.E., Merchant, S.S. (2019) Comparative and functional algal genomics. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70:605-638. for more information.

This work is funded by the DOE

We collaborate with Kris Niyogi, Mary Lipton, Trent Northen, Crysten Blaby and Matteo Pellegrini on these projects

algal-bacterial interactions

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii has been a reference organism for many decades of study, providing us with a detailed understanding of algal physiology and metabolism in axenic laboratory cultures. Leveraging this knowledge and accompanying methodological toolkit, we are examining how these algae interact with heterotrophic bacteria to shed light on roles they may play in ecological processes. We are particularly interested in how initiation of symbiotic interactions impacts algal dynamics including metabolic activity, behavior, and gene expression, and the timing and occurrence such patterns in the context of the diurnal cycle.

auxenochlorella

To address the double threat of global warming and economic vulnerability, a promising solution is to leverage the natural capabilities of microalgae to capture CO2 and convert this greenhouse gas into chemicals that can replace fossil fuels and fossil fuel-based products. We will now use our expertise and understanding of algal metabolism combined with new pathway design tools we have built to develop a practical synthetic biology platform, the Trebouxiophyte green alga Auxenochlorella protothecoides (A. pro). Our current project aims include 1) expand the A. pro. toolbox for manipulation and modification of existing and designed metabolism 2) use Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycles that incorporate bioinformatics-based enzyme discovery, engineering of lipid metabolism, and a multi-omics approach to understand system- wide design implications and 3) employ high-throughput phenotyping to increase photosynthetic capacity and resilience to light and copper-deficiency stress. Integrative systems biology and engineering of emerging model systems will expand the possibilities of microbial production of biofuels and bioproducts.